Rick Davies, Supertramp’s Steady Voice and Piano Soul, Dies at 81

9 Sep, 2025Rick Davies, the songwriter who made the Wurlitzer sing

Rick Davies, the co-founder, baritone voice, and Wurlitzer piano heartbeat of Supertramp, has died at 81. He passed away on Saturday, September 6, 2025, at his home in East Hampton, New York, after more than a decade battling multiple myeloma, a cancer of the blood. His family and former bandmates highlighted what fans already knew: his sound never shouted for attention, but it always owned the room.

Born Richard Davies in Swindon, England, in 1944, he grew up far from the London scenes that birthed many rock acts. He started on drums, found his way to keyboards, and fell for jazz, blues, and early rock ’n’ roll. That mix gave Supertramp its center of gravity—steady rhythms, soulful chord voicings, and lyrical grit wrapped in glossy arrangements built for FM radio.

He formed Supertramp in 1969 with Roger Hodgson, and the pair built a songwriting engine that was unusual even then. The credits often read “Davies/Hodgson,” but they typically wrote separately and sang their own songs. The tension between Davies’ earthier, blues-leaning voice and Hodgson’s high, airy tenor produced a catalog that sounded both sleek and stubborn. It was polished, yet never plastic.

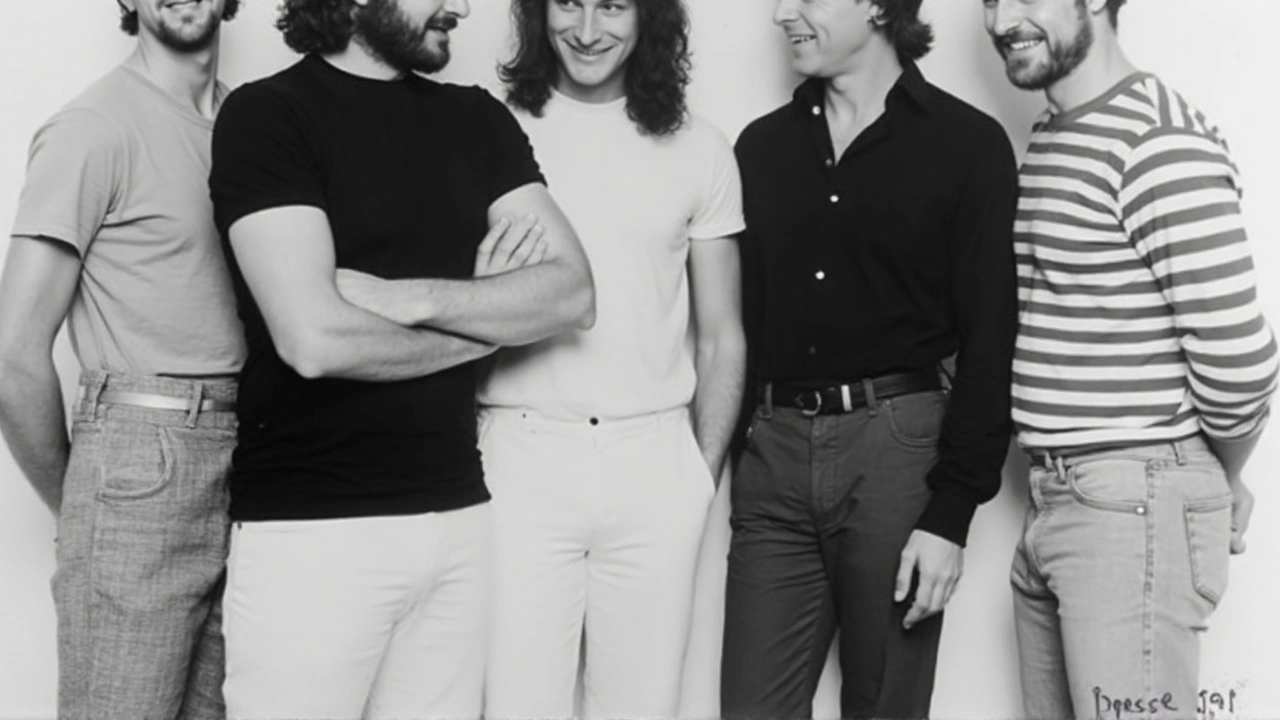

The early years were scrappy. With support from a Dutch patron in the band’s first phase, Supertramp cut two albums—Supertramp (1970) and Indelibly Stamped (1971)—that hinted at ambition but didn’t stick on the charts. Things shifted in 1974 with Crime of the Century. The classic lineup—Davies, Hodgson, John Helliwell, Dougie Thomson, and Bob Siebenberg—hit its stride. Dreamer and Bloody Well Right broke through. “Rudy” and “School” showed the band’s knack for drama without self-indulgence.

Davies’ musical signature was the Wurlitzer electric piano. It cut through mixes with a chime that could be gritty or sweet. On FM radio in the mid-70s, that sound felt like a personal message, not a broadcast. He used it to anchor arrangements that could swing from pounding, mid-tempo grooves to tender, aching ballads. The instrument didn’t just define their tone; it defined their identity.

Commercial peak arrived with Breakfast in America in 1979. The record topped charts in the U.S. and Canada, won two Grammys, and eventually sold more than 18 million copies worldwide. It sounded big but not bombastic—clever melodies, precise performances, and studio sheen that still left room for heart. The singles made the case on their own: The Logical Song, Goodbye Stranger, Take the Long Way Home. Davies’ voice—firm, conversational, unfussy—carried the songs that leaned into funk and blues. Hodgson’s tenor soared on the introspective ones.

Hodgson left in 1983 to go solo. Many assumed Supertramp would slow to a stop. Davies didn’t let it. He steered the band through the 1980s, balancing changing tastes with the core of their sound. After a pause, he rebooted the group in 1996 and kept it on the road into the next decade. The final Supertramp concert came in Madrid in 2012—a fitting close for a band that built its name in Europe before conquering North America.

Through it all, Davies kept his circle tight. He married Sue in 1977; she became Supertramp’s manager in 1984 and stayed at his side as the band evolved and, later, as his health faltered. When multiple myeloma forced the cancellation of a planned 2015 tour, the couple turned to treatment and recovery. He kept playing when he could, finding joy with local East Hampton musicians in a loose outfit called Ricky and the Rockets. It wasn’t a comeback plan. It was simply music for the sake of playing.

Multiple myeloma is a tough diagnosis. It targets plasma cells in the bone marrow and can cause bone pain, anemia, fatigue, and infections. Treatment often involves chemotherapy, targeted drugs, steroids, and sometimes stem cell transplants. Many patients live with the disease for years in cycles of remission and relapse. Davies’ decade-long fight—balanced with periods of music-making—tracked that reality.

A working-class ear that shaped a global sound

Davies’ songwriting never chased trends. He wrote in plain language, often from the point of view of a character who was restless, skeptical, or simply trying to keep life on track. He favored grooves you could feel in your shoulders and lines you could sing without sounding precious. That grounded style helped Supertramp cut through eras and formats, from vinyl to CD to streaming playlists.

His voice sits in that rare lane—recognizable from a single phrase. Not flashy, not fragile, but weighty. On Goodbye Stranger, Ain’t Nobody But Me, Bloody Well Right, and From Now On, he sounded like the steady friend at the bar who tells you the truth in a way you can handle. When Hodgson’s songs drifted into spiritual questions, Davies’ cuts argued from the street-level view. The mix gave listeners both escape and perspective.

It’s easy to file Supertramp under “progressive rock” and move on. That tag ignores what the band actually did well. They blended prog’s ambition with pop’s brevity and soul’s feel. The saxophones, the Wurlitzer, the tight rhythm section, and vocal counterpoints built arrangements that sounded intricate without calling attention to themselves. If prog sometimes drifted into self-display, Supertramp kept its head down and got the job done.

The live shows mattered, too. Supertramp’s tours were precision operations—click-tight performances, clean sound, and visuals that supported the music rather than overwhelming it. Fans who saw the band in the late 70s and early 80s remember the punch of those arrangements and the way the setlists flowed. Davies, calm and economical onstage, rarely played the showman. He let the songs carry the room.

The catalog still streams in heavy rotation today. Breakfast in America remains the gateway album, but Crime of the Century is the critics’ favorite. Even the mid-80s records, often judged against the peak years, hold moments that reveal the band’s DNA: sturdy grooves, sharp keyboards, sidelong humor, and hooks that sneak up on you. Supertramp sold tens of millions of records, but the numbers matter less than the persistence. Decades on, the tracks still sound familiar without feeling dated.

Davies also thought about the business. Through Rick Davies Productions, he controlled rights tied to Supertramp’s recordings. That mattered as the industry shifted from albums to downloads to streams. Catalogs became the backbone of modern music economics, and his stewardship helped protect a body of work that still finds new listeners on playlists and classic-rock radio.

Friends and former bandmates have described him over the years as steady, private, and stubborn in the best ways. The band’s tribute after his death echoed that: the music endures because the songs were built to last. You can hear that in the way a single keyboard stab or a lean bass line sets the scene within seconds. It’s craft, not accident.

For listeners who want to go back, a few tracks map the arc of his career:

- Bloody Well Right (1974) — the bite of Davies’ baritone and a wry lyric that became an anthem.

- Rudy (1974) — storytelling and dynamics, with the band breathing as one.

- From Now On (1977) — weary optimism over an elegant, rolling groove.

- Goodbye Stranger (1979) — sleek, funky, and radio-proof.

Even away from international stages, he couldn’t stop playing. Those small New York gigs with Ricky and the Rockets had no light show, no legacy weight, and no pressure. Just a keyboard, a band, and an audience close enough to see the chord changes. That says a lot about who he was: a working musician who kept working, even when the fight got hard.

Rick and Sue shared more than five decades together. She guided the band’s business through shifting lineups and the revival in the 1990s. She was there when the tours ended, when the clinics began, and when the music returned in smaller rooms. Their partnership was as central to the later chapters as the songs were to the earlier ones.

As fans trade memories and put the records back on, one thread runs through the comments: “These songs are part of my life.” That’s the measure that matters for an artist who never put himself above the work. The band’s farewell note captured the same idea in different words—great songs don’t die; they travel. Rick Davies sent a lot of them out into the world. They’re still moving.

by

by